How did you come up with your blog title OR what does it mean?

I thought about my two biggest obsessions, saw that they both began with “b” and that was that. At one point I would have added backpacking to the list, but I’m not so obsessed with that anymore.

What are your general goals for blogging?

I started blogging as an experiment, just to see what it was like and what it would do to my reading and writing habits. I can’t say I have anything like formal goals for blogging, but over time I’ve come to value it for the friends I’ve made, the books I learn about, and the way blogging encourages me to think carefully about what I read and to record those thoughts.

Do people “in your real life” know that you blog and do they comment on your blog OR is it largely anonymous?

Many of the people in my real life know about my blog, although not everyone. For a while I told no one except Hobgoblin, and over the three years I’ve been blogging, I’ve slowly expanded the number of people who know. Those who don’t know include some family members (some know, some don’t, and I can’t really keep track of it any more) and most people at work.

How often do you post (x per week)?

Under normal circumstances I post every other day, although this has changed over time. I started off posting every day and maintained that schedule for quite a while, but these days I’m happy posting three or four times a week — except in extraordinary circumstances where I try to give myself permission to post as seldom as I need to.

How often do you read other blogs (x per week)?

It’s more like x times per day, but I don’t feel like analyzing how much time I spend reading blogs too closely. I use Google Reader, though, which means I only read blogs when the feedreader tells me there are new posts. So the real question is how many times I check Google Reader a day, which I’m not going to divulge.

How do you select blogs to read (do you prefer blogs that focus on certain topics or do you choose by tone or…?)

Most of the blogs I read are book blogs, and then there are some cycling blogs, some blogs about other topics written by friends and family members, a couple political blogs, a few academic blogs, and a couple that aren’t in any particular category, but I just happen to like the blogger. At first I found blogs by looking at other people’s blogrolls, but these days if I’m going to find a new blog, it’s because the blogger leaves a comment here regularly. Or if a friend recommends one highly, I’ll follow it up.

Do you have any plans to copy your blog entries in any other format, 0r do you think that one day, you’ll just delete it all?

I think I signed on to some site that archives blog posts, but I forget what it is, and I don’t have any other backup system. I’m not too worried about it, to be honest; I don’t feel particularly attached to what I write here. I would be sorry if it all unexpectedly vanished, and I certainly will never delete the site, but I don’t see myself going to great trouble to preserve all my posts.

What are the things you like best about blogging?

Things I mentioned above — friends, community, book groups, ever-expanding to-be-read lists, more careful reading, and a record of my thoughts.

What are the things you don’t like about blogging?

Sometimes it can feel like a bit of a job to maintain the site, but that pressure is well worth it for all the benefits I get.

How do you handle comments? Some bloggers never respond to commenters, others answer all commenters, and still others pick and choose. (1) As a blogger, which is your practice and why? (2) As a commenter, do you care/check back to see if the blogger has responded to you? (3) If you are a reader but never comment, why (this last question may not work since…um…you don’t comment, but maybe you could make an exception?)

I try to respond to all comments, and I usually do, with an exception now and then for super-busy times. As for comments I leave on other sites, I use the WordPress feature that allows me to track comments and responses on other WordPress sites. With Blogger sites, I’ve gotten in the habit of having follow-up comments emailed to me. As far as I can tell, Typepad doesn’t have that option, so I try to check back at the site if I think there may be a comment waiting for me.

Optional: add your own topic here: any burning thoughts to share on blog etiquette? desired blog features? blog addiction? blog vs. facebook?

I discovered something annoying recently with my book give-away post: apparently there are websites that keep track of sweepstakes and give-aways and link to them so that random people hoping to win random things can enter. One such site linked to my post and sent maybe a dozen or so people my way. Once I figured this out, I started deleting comments from people who had never been here before and who I didn’t recognize. I tried to differentiate between people who read here but don’t comment regularly (who are welcome to enter the contest) and people who don’t care a thing about the blog but just want a free book (who aren’t).

At first I felt a little funny about this, but the truth is, when it comes to comments I’m pretty dictatorial — if I don’t like you, you’re out of here, and if you complain, I don’t really care. That said, I like almost everybody, and am glad you stop by.

How do you feel about deleting comments?

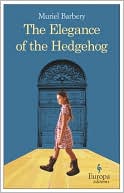

Muriel Barbery’s novel

Muriel Barbery’s novel