So I’ve been feeling a little … frustrated might be too strong a word, but something along those lines, maybe more like overwhelmed … at the fact that there are so many different types of books I’d like to read right now, and I can’t do it, even though I’ve got more reading time than usual at the moment. I’m not even talking about individual books; I’m talking about categories, within which there are dozens if not hundreds of individual books I want to read.

This is partly an issue of feeling pulled between reading widely and reading deeply, both of which I’d like to do, of course. But if I read widely, I will only read occasionally within each category, and if I read deeply, a lot of categories will get ignored. So what do I do?

I thought I’d compile a list of the categories that interest me at the moment, just for fun. This list might look entirely different on another day though. I won’t even try to make these categories mutually exclusive.

- Eighteenth-century and Romantic novels, such as the Mary Brunton one I read recently, and also Maria Edgeworth, Charlotte Smith, and Elizabeth Inchbald, plus earlier novelists like Eliza Haywood and Sarah Fielding;

- Victorian novelists — more Trollope, Eliot, and Gaskell, plus Harriet Martineau, Margaret Oliphant and late Victorians such as Galsworthy and Gissing;

- Contemporary fiction of all sorts, whatever strikes my fancy;

- Lesser-known modernists, particularly modernist women of the sort discussed here (especially Stein, Larsen, Mansfield, and Smith);

- Persephone and Virago books, such as Elizabeth Taylor, Antonia White, Radclyffe Hall, plus tons more;

- Mysteries — for my book group, but also just for myself, including finding good series and reading them all the way through;

- Random classics I’ve missed, such as Russians like Oblomov, Turgenev and more Chekhov, French writers such as Balzac and Zola;

- Okay, nonfiction. Good literary criticism, especially of the novel. More books like Nabokov’s Lectures on Literature, critical essays by people like D. H. Lawrence or Forster, and more contemporary criticism by people like Nancy Armstrong or Michael McKeon, also more philosophical stuff by people like Elaine Scarry;

- Essays and more essays — Montaigne, Bacon, Lamb, Hazlitt, Woolf, Orwell, McCarthy, Wallace, etc. etc.;

- Books on theology and spirituality, particularly ones that look at the subject from a comparative perspective;

- Science books — Brian Greene, Lisa Randall, and others;

- Biographies, particularly of writers, and most especially those by great biographers such as Richard Holmes and Claire Tomalin;

- Quirky, unclassifiable nonfiction, such as the kind of thing Geoff Dyer and Jenny Diski write;

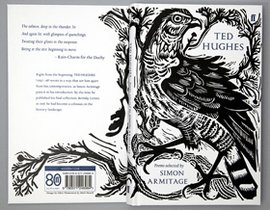

- Poetry — Romantic and Victorian poets among the older things I’d like to read, and also contemporary poetry by writers such as Louise Gluck and Mary Oliver.

What would your own list look like?

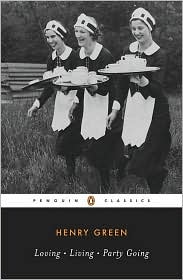

I have now finished Henry Green’s novel Loving, and while I was tempted to continue reading the two other novels in my edition, Living and Party Going, I decided to save those novels for another time. I would very much like to read more Henry Green at some point, though, because I thought Loving was very good.

I have now finished Henry Green’s novel Loving, and while I was tempted to continue reading the two other novels in my edition, Living and Party Going, I decided to save those novels for another time. I would very much like to read more Henry Green at some point, though, because I thought Loving was very good.