Mary Roberts Rinehart’s novel The Yellow Room was the latest selection for my mystery book group, and we were supposed to meet this evening at Bloodroot, which advertises itself as a feminist vegetarian restaurant and bookstore. It’s the site where the idea for the mystery group began, so it was the perfect place to hold a meeting. But the weather forecast for this evening called for lots of snow, and we cancelled. (The snow has yet to arrive, though, and it appears as though the weather forecasters may have gotten things wrong. Still, the backroads of Connecticut are narrow, hilly, and winding, and I didn’t want to take my chances.)

It appears from conversations I’ve had, emails I’ve gotten, and Emily’s post on the book that our meeting would probably have turned into a lively conversation about how bad the book is. I can sum up my assessment best by saying that as I neared the end, I didn’t care in the least who the murderer was. That’s a sure sign of a bad mystery novel if there is one, right? I was just eager for the thing to be over so I could move on to something else.

It’s been over a week since I finished the novel and the details are already beginning to fade (another bad sign); what sticks in my mind is the awkward way Rinehart moved her characters around. It seemed like they kept making the same movements from room to room, kept taking the same walks over and over again, and kept repeating the same conversations, covering a little new ground now and then to move the plot along, but not enough to make things exciting. It was wearying. I also found the characters either stereotypical, dull, or completely unbelievable. There’s a romance between two central characters, and maybe this is my fault for being a sloppy reader, but it took me a long time to catch on that this was happening, and when I did catch on, I found it completely contrived and silly. I didn’t understand why he cared about her and even more so why she cared about him.

So what is the story about? A young woman, Carol, travels to Maine to ready the family’s summer home for her brother who is on leave from the war (the novel was published in 1945), and one of the servants finds a woman’s dead body in the closet. This is the sort of thing that never happens in that small coastal Maine town, and the local police force doesn’t seem to be up for the job. Fortunately a neighbor, Jerry Dane, knows just what to do, and he conducts his own investigation, while at the same time recovering from his war injuries and wooing Carol.

The one interesting thing about the book is the way in which it is a product of its time; it’s one of those books that feels very dated, and it’s interesting to think about what makes it so. The class situation is largely at fault; Carol’s family is wealthy and spoiled, and it’s amusing to read about her awful sister who is socially ambitious and utterly heartless, and her horrible brother who is a womanizer who can’t accept that his “youthful exploits” might have some serious consequences. The novel shows how awful these people are, but there’s no sense that Rinehart is critiquing the class differences or the social system that created them. The servants are stereotyped figures, either unreliable and flighty or fiercely loyal, and I had a hard time caring that poor Carol had to manage with so few of them.

So I’m not interested in reading more Mary Roberts Rinehart, even though I did buy an edition that contains two other of her novels in addition to The Yellow Room. Fortunately, I only spent $4.50 on those three novels, so I don’t mind leaving the other two unread.

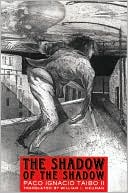

My mystery book group met this past Saturday to discuss Paco Ignacio Taibo II’s novel The Shadow of the Shadow, which was published in 1986 in Mexico. The discussion was lively, as usual, and opinions were mixed. Mine was one of the more positive views of the book; we’ve started rating our books on a scale of 1 to 10 after we finish the discussion, just for the fun of it, and I gave this one a 7 (and a couple others agreed). To me that meant that the book was a very enjoyable read, but that it didn’t blow me away or leave me determined to read lots of books by this author.

My mystery book group met this past Saturday to discuss Paco Ignacio Taibo II’s novel The Shadow of the Shadow, which was published in 1986 in Mexico. The discussion was lively, as usual, and opinions were mixed. Mine was one of the more positive views of the book; we’ve started rating our books on a scale of 1 to 10 after we finish the discussion, just for the fun of it, and I gave this one a 7 (and a couple others agreed). To me that meant that the book was a very enjoyable read, but that it didn’t blow me away or leave me determined to read lots of books by this author.