It’s time to make my list of favorite books from 2010 before we get too far into 2011. This time I will use categories rather than simply a top ten list, since my favorite books are all so different.

- Book I enjoyed most of any genre: David Foster Wallace’s A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again. I love his essayistic style.Love it.

- Favorite fiction: Nicholson Baker’s The Anthologist. Yes, this book was on my favorites list from last year, but I liked the book so much I read it again, and the second time was in 2010. Yay! Also, Paul Murray’s Skippy Dies, Joshua Ferris’s Then We Came to the End, Rosamund Lehmann’s Invitation to the Waltz, Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge, May Sarton’s A Small Room, and Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From the Goon Squad.

- Favorite mystery/crime novels: Patricia Highsmith’sThe Talented Mr. Ripley. That book is still freaking me out. Also, Raymond Chandler’s Farewell, My Lovely, not for the plot (at all!) but for the writing. Best funny mystery novels: Sarah Caudwell’s Thus was Adonis Murdered and David Markson’s Epitaph for a Tramp and Epitaph for a Dead Beat.

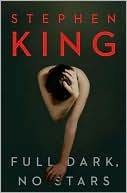

- Biggest surprises in fiction: I didn’t expect to love Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd as much as I did, but I really did love it. And Stephen King’s Full Dark, No Stars was good in a thoughtful way I didn’t expect.

- Favorite classics: My reread of Emma was awesome, of course, and I really enjoyed The Perpetual Curate by Margaret Oliphant. It was great to finally read Kafka’s The Metamorphosis as well.

- Best nonfiction: For biography, Richard Holmes’s Coleridge: Darker Reflections. I missed Coleridge when I finished reading. For essays, finishing Montaigne was great, of course, and Lawrence Weschler’s Vermeer in Bosnia was wonderful. I enjoyed Emily Fox Gordon’s Book of Days: Personal Essays greatly as well. Also in nonfiction, Jenny Diski’s book The Sixties was really good.

- Poetry: I read only two volumes of poetry this year, but they were both memorable: Faber’s 80th anniversary edition of Ted Hughes, and the poems of T’ao Ch’ien.

- Other books I liked: Samuel Beckett’s novel Molloy, I Too Am Here: Selections from the Letters of Jane Welsh Carlyle, Virginia Woolf’s Jacob’s Room, and John Williams’s Stoner.

- Biggest challenge: Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. A challenge indeed.

- Biggest disappointments: I didn’t enjoy Balzac’s novel Cousin Bette at all, and I thought I would. Also, Alicia Gimenez-Bartlett’s Death Rites was a disappointment. I didn’t dislike it as much as my book group did, but still, I hoped to like it better.

I like doing my favorites this way, because I can name lots more books!

Now for a word about my year in cycling. I rode a grand total of 6,597 miles during 2010 and a total of 409 hours (more than an hour a day!). All those miles were outdoors. My mileage in 2009, which was a record at that time, was 5,097. The funny thing about this year is that I didn’t set out to ride a lot of miles. I would have been perfectly happy riding fewer than I did in 2009. I wanted to ride exactly what I felt like riding. That’s just what I did, but apparently what I wanted to do was to ride an awful, awful lot. It was training with my Ironman friend that made the difference; she needed to go on 3,4,5,6-hour rides, and I was happy to go along. She’s not training for an Ironman in the upcoming year, so I may ride less, although I do have two other friends who will be training for an Ironman, so maybe I need to do some rides with them!