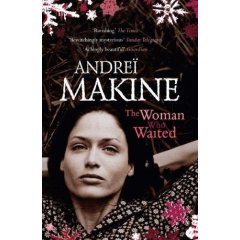

Thank you, Litlove, for recommending this book to us! Andrei Makine’s The Woman Who Waited was the Slaves of Golconda group read this time around; it’s a short novel about a woman, Vera, waiting in a small Russian village for her lover to return from the war. She’s been waiting for 30 years. Actually, what the novel is really about is the unnamed narrator’s attempts to tell Vera’s life story. The Woman Who Waited is the story of how he tries to understand who she is and why she has waited so long, instead of leaving the decaying town and forging a life elsewhere. She’s a mystery the narrative dances around.

Thank you, Litlove, for recommending this book to us! Andrei Makine’s The Woman Who Waited was the Slaves of Golconda group read this time around; it’s a short novel about a woman, Vera, waiting in a small Russian village for her lover to return from the war. She’s been waiting for 30 years. Actually, what the novel is really about is the unnamed narrator’s attempts to tell Vera’s life story. The Woman Who Waited is the story of how he tries to understand who she is and why she has waited so long, instead of leaving the decaying town and forging a life elsewhere. She’s a mystery the narrative dances around.

The narrator has come to Vera’s town, Mirnoe, on a research project; he is supposed to write reports on “local habits and customs.” His instructions are to “go and jot down a few fibs about the gnomes in their forests” and on the side he will gather material for an “anti-Soviet satire.” And so, befitting this project, he comes to the town with a detached and ironic attitude, ready to observe and pass judgment on the simple villagers clinging to their old ways.

When he arrives in Mirnoe, however, he quickly finds that the reality of the place will not let him keep his distance or maintain his ironic pose. In one episode, the narrator and Vera travel to a nearby village to persuade its last inhabitant to leave her home and move to Mirnoe. The narrator finds himself shaken by what he sees:

I went over to them, offered my help. I saw they both had slightly reddened eyes. I reflected on my ironic reaction just now when reading that sentence about Stalin ordering the defence of Leningrad. Such had been the sarcastic tone prevalent in our dissident intellectual circle. A humour that provided real mental comfort, for it placed us above the fray. Now, observing these two women who had just shed a few tears as they reached their decision, I sensed that our irony was in collision with something that went beyond it.

He sees the real human suffering that lies behind historical events, events he had only understood before in their broad sweep.

But it is the narrator’s changing feelings toward Vera that really shake him out of his detachment (some spoilers ahead). He cannot understand what motivates her to continue waiting; he cannot pierce the mystery that he sees whenever he observes her. And much of the novel is exactly that — the narrator watching Vera, following her every move, trying to figure out what she is doing, where she is going, what she is feeling and thinking. The novel’s opening portrays his attempts to understand her and the way that language fails him; we first get a sentence of description in quotation marks, as though it’s from a journal or an essay, followed by this:

This is the sentence I wrote down at that crucial moment when we believe we have another person’s measure (this woman, Vera’s). Up to that point all is curiosity, guesswork, a hankering after confessions. Hunger for the other person, the lure of their hidden depths. But once their secret has been decoded, along come these words, often pretentious and dogmatic, dissecting, pinpointing, categorizing … The other one’s mystery has been tamed.

The statement and commentary that comprise the novel’s first page show the limits of language one encounters when trying to understand another human being. The novel is a kind of unraveling, moving from this certainty toward uncertainty and surprise. The narrator never does really understand Vera, and he tries in many ways, spending time with her, talking with her, stalking her, finally becoming her lover. She always eludes him, and ultimately she proves herself to be much more sophisticated, rational, and in control than he could ever be. She may seem foolish and pathetic for having spent her life waiting for a lover who will never return, and yet she has found peace and beauty and a kind of contentment.

The novel’s writing is beautiful, spare and suggestive; it captures the landscape of northern Russia with its forests, lakes, and snow. It makes me long to be there. I must admit that this is one of those books that I’m liking more and more as I write about it; at first my reaction was admiring but a little dispassionate. The more I think about it, though, the more I appreciate what a wonderful creation Vera is and what a powerful evocation Makine has given us of one person’s fumbling attempts to grapple with the mystery of another life.

Dorothy – you write so exquisitely about this novel! What a beautiful review! And I’m so glad you liked the book. It certainly grew on me, too.

LikeLike

Lovely review and I definitely think I will try to read this book this month or next – the premise sounds wonderful and I’ve been wanting to read Makine for a while now.

LikeLike

I really like books that become more important as you think about them. When the book refuses to leave your consciousness and you find yourself still puzzling about motivation and behavior, still trying to solve the mystery to your own satisfaction…

LikeLike

This book has been on my ‘to read’ list and now that I have seen what you and Litlove say, I will definitely read it. Thank you for such a great review.

LikeLike

This book was double-booked at the local library so I couldn’t get it in time to read it. Maybe I should plunk down money for an actual purchase.

LikeLike

Thank you Litlove! I do love it when books grow on me — I think I like them better when I come to appreciate them over time rather than all at once.

Verbivore — oh, do give it a try, especially as you’ve been planning on it for a while! I’d love to hear what you think.

Jenclair — yes, you describe that pleasure perfectly! And it’s fun to work out the meaning of a book with a group of people, which is why I appreciate the Slaves group so much.

Becky — thank you! I appreciate Litlove for pointing it out because I’d never heard of the title or the author before.

Imani — well, I’d hate to advise you to buy something and then be wrong about it … but it may be worth while …

LikeLike

Sounds great to me. Maybe if I do the Russian challenge, this can be a short one for the list.

LikeLike

wow, dorothy, what a great book review! I feel compelled to read this immediately after reading your review. 🙂

LikeLike

Hi Dorothy, I used to have a blog called “The Bicycle”. Perhaps you remember me. I’m glad I found your new blog location.

I haven’t read this Andrei Makine novel, but I think I will now. There seem to be many Tolstoyan echoes – the connection (or lack thereof) between intelligentsia and rural people, the use of perspective, the whole plot reminds me of certain aspects of Cossacks.

LikeLike